This exhibition celebrates two legendary figures with tremendous significance to this museum and its encompassing communities in the university, city and state. Harvey Dunn is a source of pride and inspiration for South Dakotans, known to many as the most famous artist this state has had the honor of claiming as its own. Born on a homestead near Brookings, Dunn attended South Dakota State University in 1901 (then known as South Dakota Agricultural College). Ada Caldwell was 32-years-old and had been teaching art as a professor of Industrial Art at the college for just two years when he arrived. She recognized his immense talent and cultivated it, steering him towards his fateful course.

The title of the exhibition, "The Sea and The Land and The Sky," is drawn from a Christmas card produced by Gertrude Stickney Young, a close friend of Caldwell’s and a professor of History at the college. Young would use her writings along with Caldwell’s images in these cards. It seemed a fitting title for this show, which is focused on landscapes by both Ada Caldwell and Harvey Dunn.

About

As Dunn has said about her importance to him in that first year:

"I took the Art and there met that little lady, Ada B. Caldwell, who opened new vistas for me. For the first time I had found a serious, loving and intelligent interest in what I was vaguely searching for. She seemed to dig out talent where none had been and she prayed for genius. She was tolerant and the soul of goodness. With my eyes on the horizon, she taught me where to put my feet." - Harvey Dunn

After a year of study, Caldwell encouraged Dunn to move on to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, her alma mater, in order for him to receive more advanced training. There he was discovered by the famed “Father of American Illustration,” Howard Pyle, who recruited Dunn for his elite illustration school. After two years of study with Pyle, Dunn entered into an illustrious career in the booming field of American illustration.

Over her, nearly four decades of teaching at the “college on the hill,” Caldwell’s discerning eye, skillful hands and compassionate commitment to excellence in teaching would be recognized by many more after Dunn. She was known as an inspiring visionary, who worked tirelessly in service to students, the college, the community and the arts. Her great desire to make the arts an important part of the cultural life of South Dakotans laid a foundation that has had an exponential, multi-generational impact.

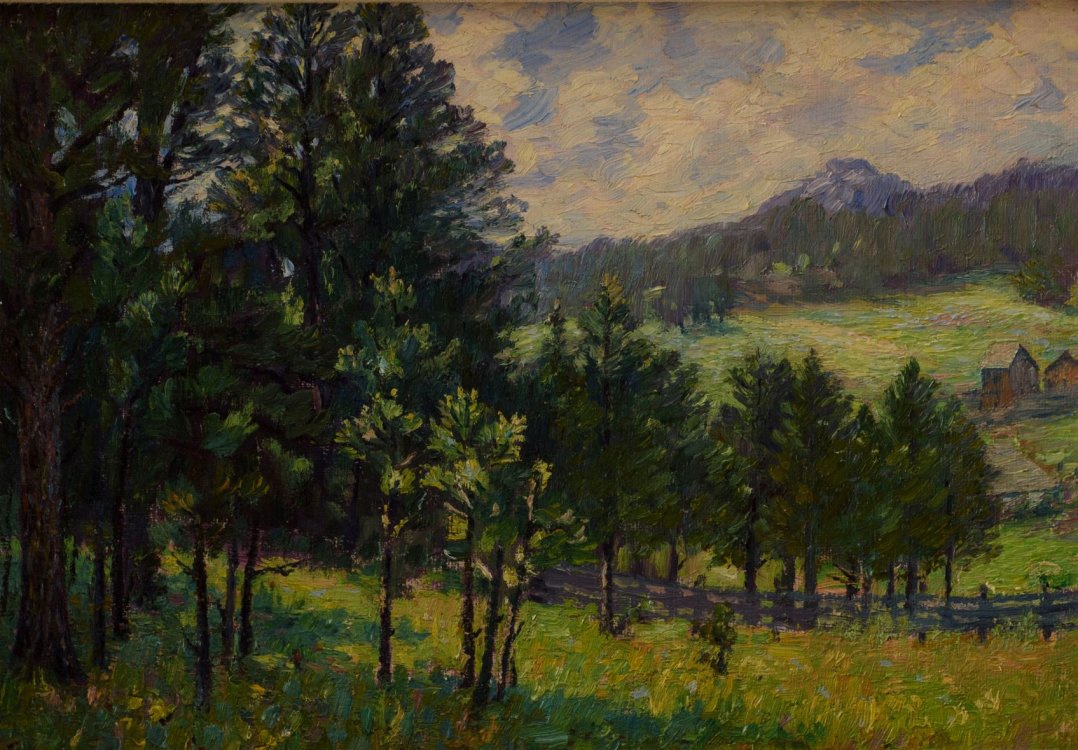

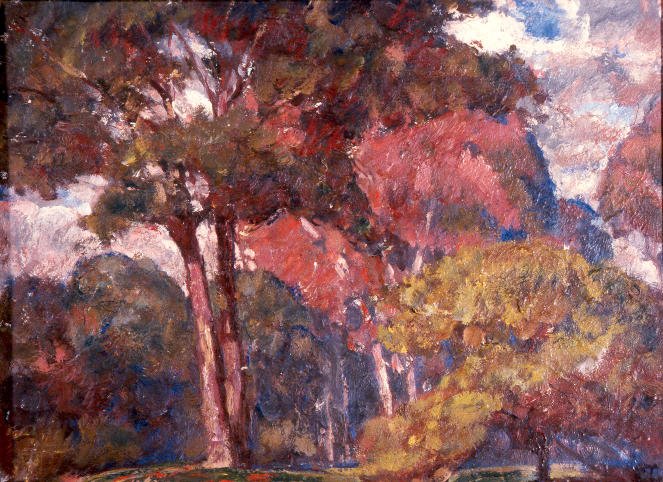

Landscapes were a favorite subject of Caldwell’s. She was adept with a range of media and created fine crafts and design work as well, but the majority of her works in the museum’s collections are landscape paintings. Quite apparent in these are Caldwell’s love of the beauties and moods of the land and her skill in capturing this poetic majesty with painterly virtuosity.

From quick sketches to more developed pieces, all of the museum’s pure landscapes by Dunn are on display. They are as devoid of figures as possible, with the exception of a selection of prairie paintings. The richness of the land and sky in these merit consideration, despite their inclusion of more than just “natural” scenery. In no small way, these figures are folded into the land’s richness—perhaps becoming a natural extension of it themselves.

Caldwell instructed how to break down complicated landscapes in her lesson “Color as Seen in Nature.” At the core of this she instructed that the plane of the sky, the source of light, was lightest in value; the horizontal plane of earth or sea, receiving the most direct light from the sky, was the next lightest and the upright plane of trees and buildings, with light falling on them least directly, were lowest in value. Dunn is most famous for his prairie paintings, illustrations and war works but, like Caldwell, landscapes were an important part of his teaching and practice. In order to learn “what takes place in nature at all times and under all conditions,” Dunn’s students would paint landscapes regularly. They drew complicated outdoor scenes in pencil on very small sketch pads in three tones, just as Caldwell had instructed. Dean Cornwell, one of Dunn’s most famous students, said “it was the most valuable training of any I can recall.”

Both Caldwell and Dunn owe much to a painterly tradition, with visible brushstrokes and thick wet-into-wet paint application in their works. Despite all similarities, the artists show their unique signatures in the handling of media. The elegant, refined, delicacy of Caldwell’s touch and the vigorous, bold, expressive qualities of Dunn’s makes for an interesting contrast in personalities. It is hard to not see the differences between the artists themselves in the differences between their styles—Caldwell and her paintings as “little” and “gentle” but “sparkling with gayety,” Dunn and his paintings as “whales” filled with “rustic gusto.”

If such categorizations didn’t seem outdated, narrow and stereotypical, it would be tempting to characterize this as a dichotomy of the feminine and masculine. Perhaps more interesting and illuminating is the fact that each artist used the tools of art to create balance, thereby preventing what was dominant from dominating, in both art and life. As Dunn has said, “without strength there is no tenderness.” Tenderness becomes fragility without strength and strength becomes cruelty without tenderness. In the effort to create a balanced whole, both of these artists appreciated the necessity of everything in good measure. As teachers, they both also respected that in addition to learning the foundational lessons of art-making each student needs to learn to find their own unique strength, emphasis and balance. The works of these educators embody these timeless lessons. We are fortunate that they are still teaching.