Present in nearly half of Dunn's works in our collection, fences, cows, plows and oxen were a common feature of the subsistence lifestyle that South Dakota's settlers relied on in the pioneering era of Dunn's youth. This exhibition celebrates these prairie paintings and the roots of South Dakota's agricultural heritage.

The Homestead Act of 1862 opened federal lands in the United States to settlement by small farmers at affordable prices, hastening the settlement of western territories. A requirement of the act was that settlers had to live on the land for five years and improve it in order to be granted full title to it. Along with the influx of homesteaders to the West came the tools of their trade: fences, cows, plows and oxen.

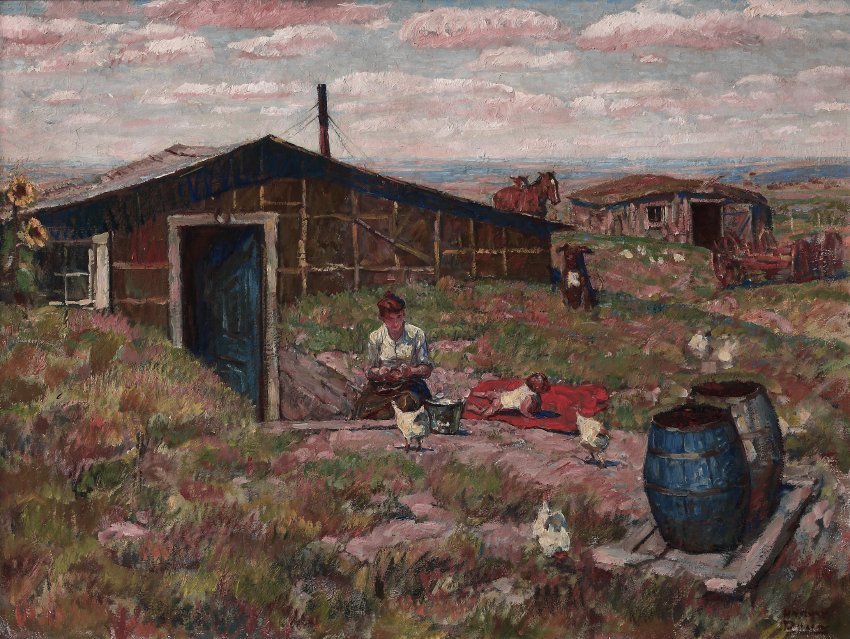

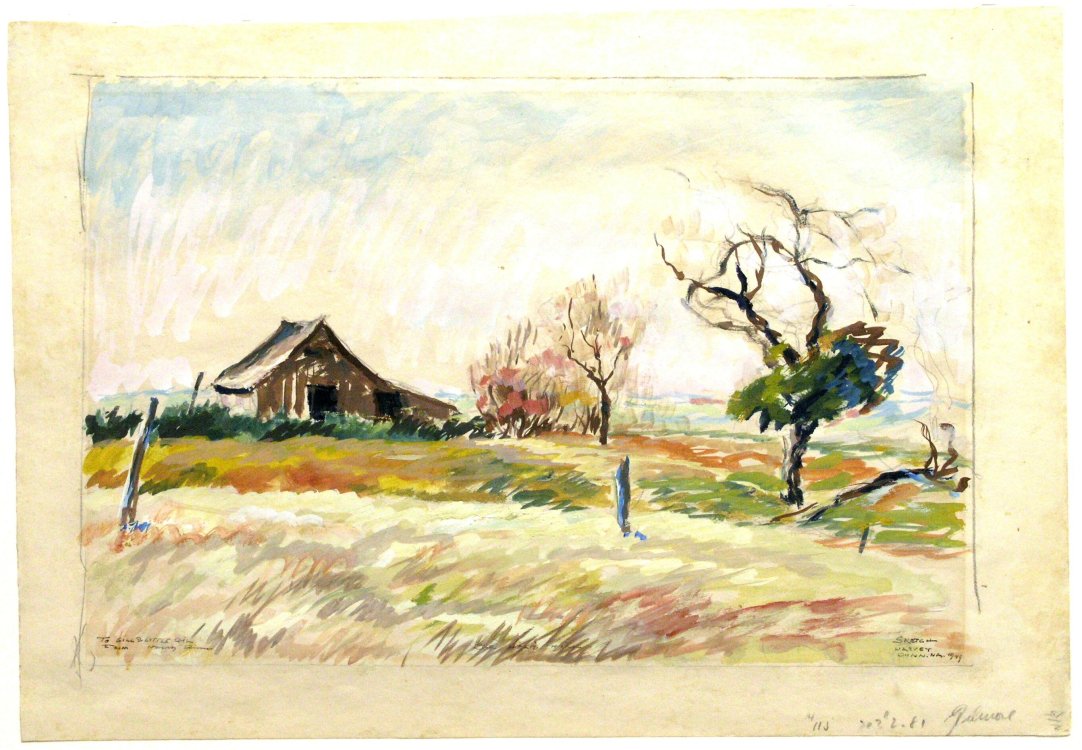

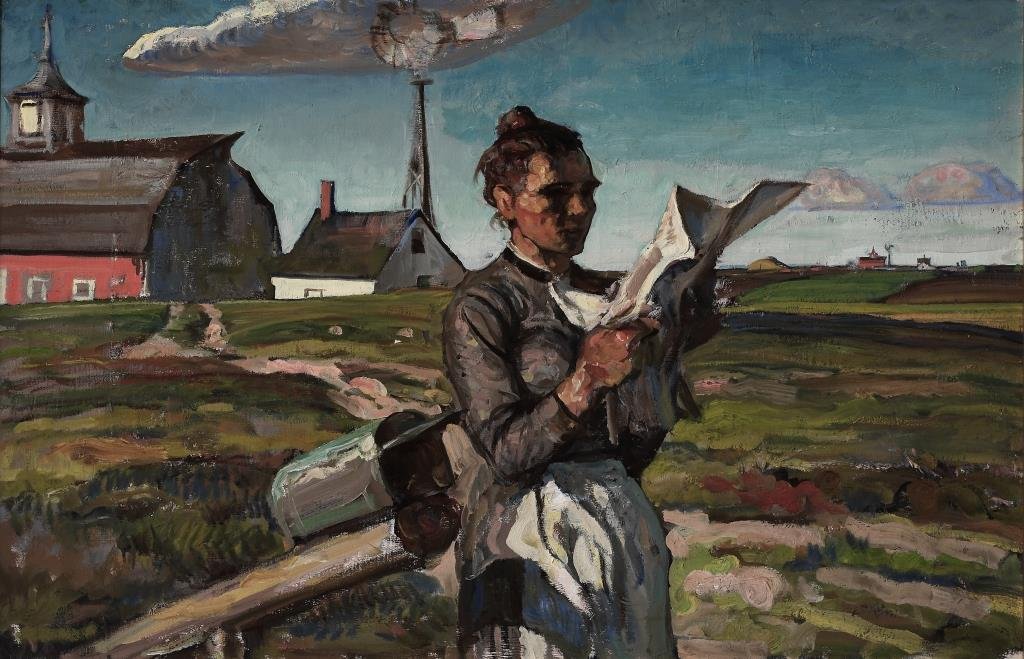

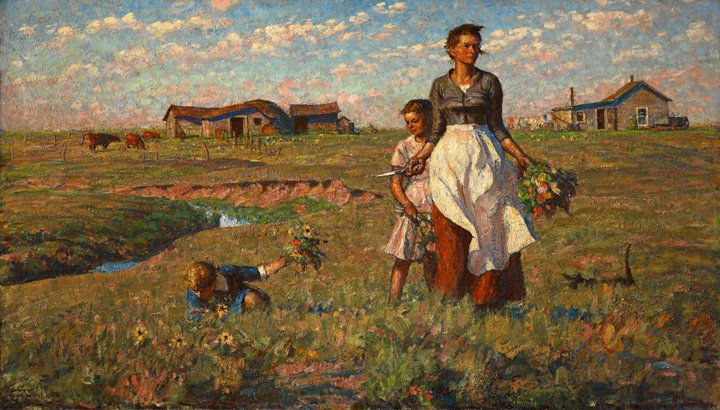

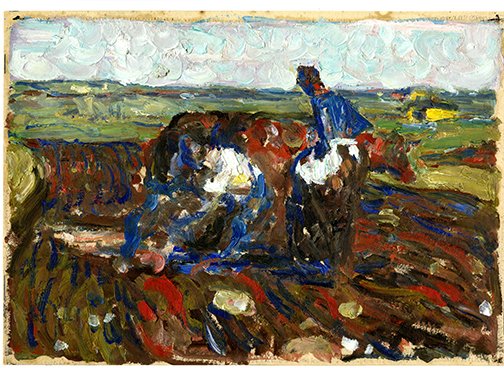

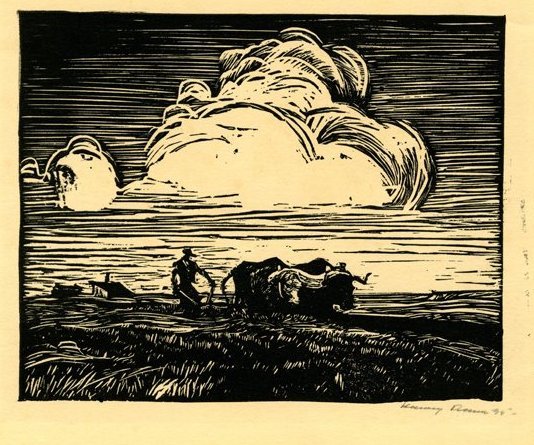

"Harvey Dunn: Fences, Cows, Plows and Oxen" celebrates the hard-working agricultural backbone of the state of South Dakota. Born to South Dakota homesteaders in 1884, Harvey Dunn’s paintings of this place, that era and the agricultural lifestyle that it resulted in are often littered with these ubiquitous and essential features of homesteading life on small family farms. Dunn’s imagery shows families heading west, hard at work, breaking sod, plowing the land, driving oxen, fixing fences, herding and milking cattle, braving storms and cold and tending to the affairs of everyday life on the homestead or farm.

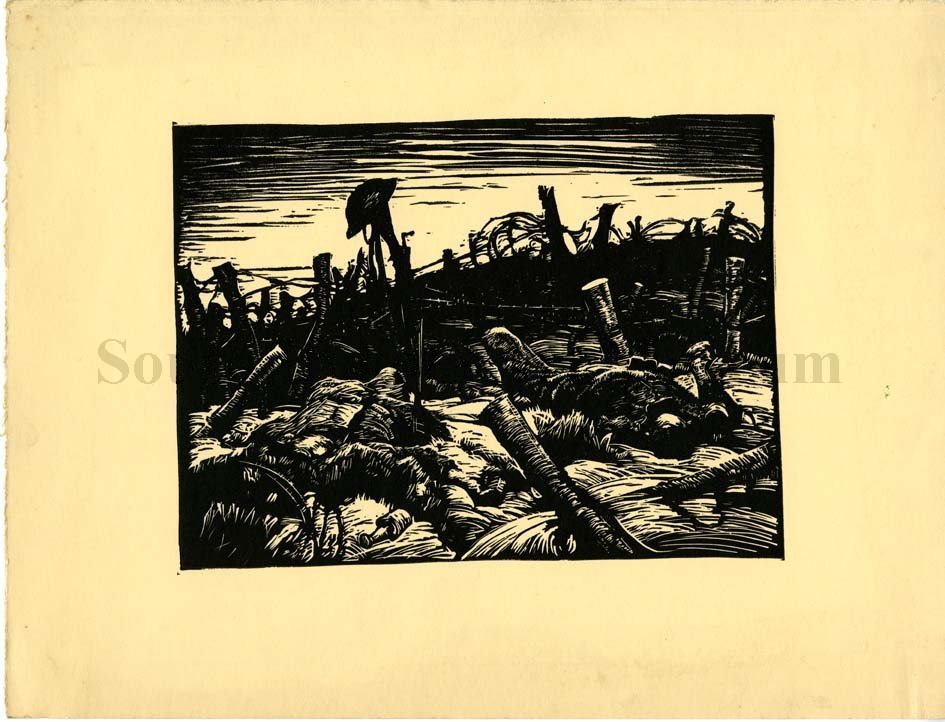

In some of these images the fences, cows, plows or oxen take center stage, becoming characters within the painting themselves. In others, they are barely referenced as small masses in the distance, or faint, slight lines dotting the landscape. A smaller number of images allude to a more disconcerting legacy of the heydays of homesteading. Paintings of deserted houses, abandoned farms and old settlers stand as relics of a bygone era. Barbed wire, invented in the 1860s and used as a cost-saving way to restrain cattle in the wide expanses of the West, can be seen in Dunn’s World War I images. The grisly effects of its use as a part of trench warfare fortifications are apparent.

Harvey Dunn (1884—1952)

Harvey Thomas Dunn was born near Manchester on March 8, 1884. The son of homesteaders, he attended a one-room schoolhouse with his brother and sister and helped his parents work the soil. His talent for art was recognized early on and encouraged by his mother.

In 1901, Dunn began studying art at South Dakota Agricultural College (now South Dakota State University) with a young instructor named Ada B. Caldwell. After a year of school, Caldwell urged Dunn to attend her alma mater, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in order to receive training beyond what she could offer.

With money earned from working as a farmhand, Dunn enrolled at the Institute and attended from 1902 to 1904. It was there that he met America’s foremost illustrator, Howard Pyle. Pyle was so impressed with Dunn’s work that he extended an invitation for the young artist to come and study at his prestigious school of illustration in Wilmington, Delaware.

After studying with the master for two years from 1904 to 1906, Dunn opened his own studio near Pyle’s in Wilmington. Almost immediately, he became a successful illustrator and was soon creating illustrations for numerous books and periodicals, including Scribner’s, Harper’s, Collier’s Weekly, Outing and The Saturday Evening Post.

After Pyle’s death in 1911, Dunn moved his studio closer to the art market and publishing companies of New York City, settling in Leonia, New Jersey. As he grew in stature as an illustrator, he became more concerned with encouraging other artists, as he had been encouraged by Ada Caldwell and Howard Pyle. In 1915, he and fellow artist Charles Shepard Chapman established the Leonia School of Illustration.

Harvey Dunn’s career was interrupted when the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. At age 33, Dunn was one of eight artists chosen by the American Expeditionary Forces to document and illustrate the war for purposes of propaganda, recruitment and public education. After he returned from the war, Dunn’s interest in commercial illustration declined. He hoped to continue working for the War College by completing paintings from his many field sketches. When this project was rejected, Dunn moved his family to Tenafly, New Jersey, where he re-established himself as an illustrator but gave himself more zealously to his teaching. “All that I am really doing,” he said years later in speaking of his own school, “is carrying on the Howard Pyle idea.”

Beginning in 1925, Dunn started making regular treks back to South Dakota. It was during this period, from 1925 to 1950, that he created the bulk of what would become known as his prairie pioneer paintings.

In 1950, at the Masonic Lodge in De Smet, Dunn held the first exhibition of his works in South Dakota. Moved by the public response to his exhibition, he gifted most of the works from that show to the people of South Dakota, forming the foundation of the South Dakota Art Museum’s collection. Dunn passed away shortly thereafter, in Tenafly, New Jersey, on Oct. 29, 1952.

Artworks in Fences, Cows, Plows and Oxen

30 Below, A Driver of Oxen, After School, Badlands, Breaking Sod, Buffalo Bones are Plowed Under, Dust, Fixing Fence, Girl Driving Oxen, Going West, Home, Homesteader’s Wife, I Am the Resurrection and the Life, Joe Holt’s Hill, Just a Few Drops of Rain, Old Settlers, Patience, Prairie Farmer’s Wife, R.F.D., Settlers in Canada, Something for Supper, study for “The Stoneboat,” Storm Front, The Abandoned Farm, The Deserted House, The Devil’s Vineyard, The Homing Herd, The Prairie is My Garden, The Stoneboat, The Sunlit Hills, The Visit, untitled, untitled (plowing with oxen), untitled (woman milking a cow) and untitled (WWI)